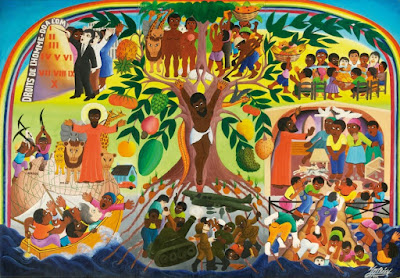

The Tree of

Life, by Jacques-Richard Chery (Haiti)

For more details, look it up here.

Ezekiel 47:1-12

47 Then he brought me

back to the entrance of the temple; there, water was flowing from below the

threshold of the temple toward the east (for the temple faced east); and the

water was flowing down from below the south end of the threshold of the temple,

south of the altar. 2 Then he brought me out by way

of the north gate, and led me around on the outside to the outer gate that

faces toward the east; and the water was coming out on the south side.

3 Going on eastward with a cord in his hand, the man measured one

thousand cubits, and then led me through the water; and it was

ankle-deep. 4 Again he measured one thousand, and

led me through the water; and it was knee-deep. Again he measured one thousand,

and led me through the water; and it was up to the waist. 5 Again

he measured one thousand, and it was a river that I could not cross, for the

water had risen; it was deep enough to swim in, a river that could not be

crossed. 6 He said to me, “Mortal, have you seen

this?”

Then

he led me back along the bank of the river. 7 As I

came back, I saw on the bank of the river a great many trees on the one side

and on the other. 8 He said to me, “This water

flows toward the eastern region and goes down into the Arabah; and when it

enters the sea, the sea of stagnant waters, the water will become fresh. 9 Wherever

the river goes, every living creature that swarms will live, and there

will be very many fish, once these waters reach there. It will become fresh;

and everything will live where the river goes. 10 People

will stand fishing beside the sea from En-gedi to En-eglaim; it will be a

place for the spreading of nets; its fish will be of a great many kinds, like

the fish of the Great Sea. 11 But its swamps and

marshes will not become fresh; they are to be left for salt. 12 On

the banks, on both sides of the river, there will grow all kinds of trees for

food. Their leaves will not wither nor their fruit fail, but they will bear

fresh fruit every month, because the water for them flows from the sanctuary.

Their fruit will be for food, and their leaves for healing.”

Revelation

21:1-6, 22-26; 22:1-5

21 Then I saw a new

heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed

away, and the sea was no more. 2 And I saw the holy

city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a

bride adorned for her husband. 3 And I heard a loud

voice from the throne saying,

“See,

the home of God is among mortals. He

will dwell with them;

they will be his peoples, and God

himself will be with them;

4 he will wipe every tear from their

eyes.

Death will be no more; mourning and

crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.”

5 And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making

all things new.” Also he said, “Write this, for these words are trustworthy and

true.” 6 Then he said to me, “It is done! I am the

Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end. To the thirsty I will give

water as a gift from the spring of the water of life.

22 I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God

the Almighty and the Lamb. 23 And the city has no

need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its

lamp is the Lamb. 24 The nations will walk by its

light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. 25 Its

gates will never be shut by day—and there will be no night there. 26 People

will bring into it the glory and the honour of the nations.

22 Then the angel showed me the river of the water of life,

bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb 2 through

the middle of the street of the city. On either side of the river is the tree

of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, producing its fruit each month;

and the leaves of the tree are for the healing of the nations. 3 Nothing

accursed will be found there any more. But the throne of God and of the Lamb

will be in it, and his servants will worship him; 4 they

will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. 5 And

there will be no more night; they need no light of lamp or sun, for the Lord

God will be their light, and they will reign forever and ever.

A

‘cutting’ of tree wisdom (Genny Tunbridge)

Wisdom is like a baobab tree; no one individual can embrace

it [1]

Baobabs trees are native

to Madagascar, mainland Africa, and Australia, and were introduced to the

Caribbean in the colonial era. They can store up to 120,000 litres of water in

their massive bottle-shaped trunks, and they are deciduous, leafless for 9 months

of the year during the dry season to conserve water. The thin, twisty branches

look more like roots, so the baobab is sometimes known as the ‘Upside Down

Tree’. Myths and stories about baobabs abound, many explaining their

appearance. In one, the baobab is always complaining, so God uproots it and

replants it with its head in the earth and roots in the air! Since then the

baobab has stopped complaining and become the most useful tree around.

‘Tree of Life’ is another

name often given to baobabs, reflecting their longevity (some live over 2000

years) but also that they provide almost everything humans need to survive,

including water, shelter, clothing and food. The bark and huge stem are used

for making cloth and rope; the leaves are used as condiments and medicines; the

fruit is edible, rich in vitamin C. The hollow trunks of old baobabs were

sometimes used as tombs for griots (traditional storytellers) – the trees

perhaps believed to absorb and preserve the history and traditions contained in

the griot’s words. Did enslaved Africans on Caribbean plantations draw

inspiration and strength in turn from the wise baobabs, transplanted like them

in a foreign land.

“Knowledge is a light

that is in man; it is the inheritance of all that the ancestors knew and sowed

deep within us, just as the power of the baobab is contained in its seed.”[2]

Introduction to the theme (Al Barrett)

We’ve come again to the turning of the seasons. This week is

the last of our 5-week season focusing on Black History Month and racial

justice. And the inevitable question is, what next? The danger with any

‘themed’ season (just as with our previous season focusing on Creation) is that

we quickly forget – we put it behind us, and turn our attention to something

else. We ‘move on’.

But like Ezekiel in his vision, where we go next is not away

from the river, but deeper into its flow. Next week, and for the four

weeks of November, we’ll be wading further into the waters of remembering: a

remembrance of those we have loved and lost personally, those who have died in

the wars and conflicts of our world, and those saints who have walked the way

of faith before us. And that remembering will be both looking back, to

the past, but also looking forward: ‘remembering the future’, with the

hope-filled promises of God in the words of the prophets of Scripture and the

lives and witnesses of the saints that light our way.

So this week, at the turning again of the seasons, we turn

back to ancient texts that point us towards a future that is still ahead of us:

a universe renewed, ‘a new heaven and a new earth’, a ‘heavenly’ city that is

planted firmly in God’s good earth, a garden city that might be called

‘Jerusalem’, but also ‘Eden’. Here, we’re told of a city whose gates are always

wide open, never shut. A city where whatever glory ‘nations’ used to have, now

pales into insignificance before the glory of God. A city where there is no

more death, no more fearful night-times, no longer any mourning, crying or pain

– a promise for all who have ever grieved, but especially for all who have ever

been oppressed, enslaved, marginalized. A city where there is enough food for

all – and where all have what they need. A city where, as God walks the streets

and climbs the trees alongside her children once again, old wounds are healed –

wounds not just of bodies and minds, but wounds of relationships between

peoples and nations, between humans and our creature-kin, and with the earth

itself. This is a city where the journey of reconciliation has run its course,

and has come to its Source.

But how do we get there from where we are now?

Neither the world we live in, nor the Church of today, are the new Jerusalem.

The water that flows from Ezekiel’s Temple, bringing refreshment, cleansing and

teeming life to the stagnant places of the world, has been dammed up, siphoned

off or poisoned; and what flows out from the Church’s sanctuaries, in the name

of love, is too often polluted with anxious institutional self-interest, the

misuse and abuse of power, or a kind of ‘broadcasting’ that’s indifferent to or

ignorant of the reality of the life of our neighbours. Even when we talk the

language of ‘reconciliation’, it can all too easily become a manipulative word,

that we imagine we can use to engineer change ‘out there’ – to get everyone to

just start being nice to each other – without the discomfort, pain and

costliness of changes in us and the ways we live our lives.

That radical change the Bible calls repentance:

literally, a ‘turning around’. And that, as we’ve seen over the course of this

month, involves some other ‘R’ words too:

REMEMBERING… We’ve been reminded, in this Black History Month, that

history matters. We may not be personally responsible for what happened

in the generations before we were born, but it has left its mark on us

nevertheless – in benefits or disadvantages, in collective wounds and traumas,

in the shaping of attitudes, relationships and structures in the present. We

remember the past, because its legacy lives on in the present – and we need to

continue the work of disentangling what is worth celebrating, from what is in

need of healing.

RECEIVING… We’ve been blessed, over these last months, by being able to read and

hear ‘5th gospel’ reflections on the lived experiences of many

different members of our congregation – and not least during these last few

weeks of Black History Month. Some of those ‘testimonies’ have been hard to

write and speak – and also hard to hear, especially for those of us who are

white to hear of painful experiences of racism in the world, and in the church.

But those stories, those acts of honest sharing, have helped reveal for

us something of the truth, the reality of the world we all share. As the singer

and poet Samantha Lindo puts it, they have been contributions to ‘naming the

water in which [we] swim’.[3]

RELINQUISHING… We’re discovering, I think – especially if we’re white, and

even more so if our identity brings with it other kinds of privilege too (male,

middle-class, non-disabled, etc) – that if we’re to truly hear the stories,

truth and witness of others, if we’re to truly receive the challenges in what

we hear and what we remember, in ways that will change us… then there’s some letting

go that we have to do. Letting go of some of our defences and

defensiveness, letting go of our tendencies to jump in too soon with words or

actions (or to try and have the last word), letting go of our need to be

‘centre stage’, to be ‘needed’, or to be the person that ‘fixes’ things. Some

of us are so used to being listened to, looked to, and holding on to our

positions of comfort and status, that any kind of letting go can feel painful,

costly. But it’s necessary. There’s no way round it.

REPARATION… As we encountered with Zacchaeus last week, if repentance

is to be real, it needs to be more than a change of heart. The way we relate to

each other, the way the systems work, the circumstances of our neighbours need

to start to change too. The water of life, where it has been dammed up, needs

to be unblocked to flow freely. The fruit of the garden, where it has been

hoarded for the few, needs to be shared in ways that mean no one goes hungry.

The wealth that has been built up through the forced labour of slavery, and

through many other injustices in our world, needs to be redistributed. The

power that has been held on one side of dividing lines of race, class and

gender (among others), needs to wash the barriers away. And where we have been

a beneficiary of these things, we need to play our part in ‘putting things

right’ in ways that are real and tangible, and potentially costly – in our

relationships, our communities, our society, our world.

Over the past few weeks, many of us who are white have heard

stories, and been part of conversations, where we’ve felt ashamed of the

history that we’re part of, and the structures we’re entangled in – and where

we’ve felt guilty about what we’ve done, or not done, ourselves. Shame and

guilt, as we saw in the story of Adam and Eve in Genesis 3, can make us want to

hide, can paralyse us. But as we hear God calling us to come out from behind

the tree, as we come face to face with God and face to face with each other

(which also means coming face to face with ourselves), then we discover

ourselves also called to take the next step on a journey – a journey towards

the new heaven and new earth.

Reflection (Revd Dr Carlton Turner)

Carlton

is an Anglican priest and tutor at The Queen’s Foundation for Ecumenical

Theological Education.

These readings, what we call apocalyptic readings, always

fascinate me. In fact, that final scene from the Book of Revelation always

brings me a deep sense of peace and joy. Having grown up in the Caribbean and

having studied the history and legacies of slavery and colonialism, I am

reminded that the ultimate purpose of God isn’t simply justice, but healing and

wholeness: “See,

the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his

peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death

will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be

no more, for the first things have passed away (Rev.

21:3-4).” In this reflection I want us to hold on to this idea and hope of

total healing that seems to be the last word throughout the pages of the Bible,

both Old and New Testaments.

In our passage from Ezekiel 47 we

find a vision of a river flowing from God’s temple. As the scene is described,

we become aware of the dynamic nature of this river. Firstly, there is evidence

in the translation of the text to suggest that the river begins as a trickle from

the temple. It starts small but becomes increasingly deeper and more powerful. The prophet is led through this

water by the angelic being, but the further they go, the deeper the river gets.

It eventually becomes overwhelming and they must return to the riverbank. Then,

the deeper truth is revealed about this water trickling from the temple, that

becomes an overwhelming river; It brings healing and renewal wherever it goes.

In fact, the trees and their leaves that are supplied by this water are for the

healing of the nations.

Nonetheless, it would helpful

if we remember that the beauty and power of this imagery comes in the midst of utter chaos and desolation. Jerusalem

is a city that has no river or stream. Cities were usually built upon rivers

and streams for their sustenance and defence. Ezekiel is writing in the memory

of the destruction of the Jerusalem temple and the first deportation of the

Jews to Babylon. You can inject that famous reggae re-chanting of Psalm 137:1:

“By the rivers of Babylon, where we sat down, and there we wailed, when we

remembered Zion!”

We find the same imagery in Revelation 22:1 – 5. The river

flows from God’s throne and it flows through the Holy city. On either side of

the river is the Tree of Life that is meant for the healing of the nations. But

again, we would do well to remember that this last chapter of the Bible is

speaking such amazing promises in the context of predicting war, destruction,

persecution and death. War breaks out in heaven that reflects the very reality

of war on earth. Every successive human civilisation has had to experience

these absolute horrors, and yet, in the midst of these unspeakable images,

there is the God who comes and abides with His people, and then wipes every

tear from their eyes. And, when we look at the text more deeply, we realise

that it promises, as Isaiah 11 does, a peaceable kingdom: there is neither

hunger, nor pain, nor death; neither predator nor prey; neither chaos nor war;

there is only shalom!

We are now at the end of Black History Month in our

observances and this message of healing is appropriate. The story of Black

people in the world is not an easy one to come to grips with. At the beginning

of the month Al introduced the themes that we have been reflecting on. In it he

points to the long history of Black oppression, marginalisation,

criminalisation, and exclusion, and even genocide. The Transatlantic slave

trade, brutal plantation slavery and colonisation, were undergirded by a

philosophical, theological, and sociological idea that blackness was taboo, and

that black people were beast of burdens, without the right to freedom and

autonomy. The legacies of this are clear for the British context: the Windrush

scandal; the murder of Stephen Lawrence and the resulting Macpherson Report;

statistics within the prisons or mental health institutions that have racial

indications; Covid-19 and its exposure of the racial/ethnic face of ill-health;

and then the aftermath of the public killing of George Floyd! Added to this,

the Church of England is being charged with ‘institutional racism’, with books

such as Ben Lindsay’s We Need to Talk about Race, and Azariah France-Williams’

Ghost Ship interrogating the deep institutional nature of racism in British society, including

the Church. But, beyond all this,

there are the internalised wounds that Black people carry; wounds that have

been handed down, and that undoubtedly will be passed on. The biggest question

remains, where is the healing, where is the shalom?

I believe that deep within the wounds of the Black experience

there is a hopefulness and a healing that resides within our lament. A point I

make in my own writing is that slavery wasn’t an event that happened to Black people, but one that they

survived! They survived through their indigenous religious and cultural

observances such as their music, their religious traditions, their proverbs and

their story telling, and their ingenuity and creativity. It is fair to say that within the very wounds of

slavery, anti-Africanness, and racism, Black people also have a deep reservoir

of sacred power, or creative spirituality, that surges to the surface

coming out in Reggae, in Soca, in Gospel Music, in pop music, in carnival, in

Pentecostal worship, and even in the alternative spirituality of the Rastafari.

What I’m suggesting is that healing for Black people comes in the midst of

their pain. These means of healing above have been so powerful that Church and

society have often worked hard to criticise or demonise them.

As we move into another month and another observance, I

encourage us to remember the need for healing, and the potent forms of healing

that Black culture possesses. Perhaps, these ways of being, acting and seeing

the world will not only be of benefit for Black people, but for all people.

They will be, in a way, like the deepening River of Life, or the Tree of Life;

they are for the healing of the nations, the healing of all people. Let’s end

with the deep lament within Psalm 137 that the African Caribbean experience

brings alive for us:

By the rivers of Babylon,

there we sat down

Yeah, we wept, when we remembered Zion

There the wicked

Carried us away in captivity

Requiring of us a song

Now how shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?

Let the words of our

mouth and the meditation of our heart

Be acceptable in thy sight here tonight

By the rivers of

Babylon, there we sat down

Yeah, we wept, when we remembered Zion…

(Lyrics by Boney M)

Reflection (Sybil Gilbert)

I was born in Kingston Hospital. All my life I was the

weakling of the family. I spent so many times in hospital, if anyone mentioned

the word I would have a panic attack. My first encounter with hospital was when

I was a baby in a cot. My cot was looking out of the window. It was late at

night, I could hear a noise and saw nurses or people wheeling trollies past my

window. The worst thing the nurse could do was to move my cot away. I was so

afraid. It was the middle of the night, and no one would explain to a curious

child what was going on. Some years later a cousin of mine explained that there

was an epidemic and several children had died. I asked him to take me to the

morgue. I wanted to know what happened when you died.

My grandmother’s was the first funeral I can remember

attending. My young cousin who was a ‘towny’ did not want his feet getting

dirty so he sat on my shoulder the whole time. I can remember her coffin was

made in the village, it was lined in purple, beautiful velvet. My gran-mom

smoked a pipe. My cousin Beverley said that now Grandma had died the pipe was

hers. She decided to put some dried yam leaves and lit the pipe. There was an

outside toilet, a small one for the children. It was a good thing she sat on

the child one or else she would have fallen in the pit. It took days to sober

her up! Her parents, my favourite uncle Leslie and Aunt Chris, were very cross.

But they could not help laughing. It was the only time I had rabbit to eat and

never again. Grandma is buried at the back of her home. It was a family plot.

The land was given to her and the family by my grandfather who was a Jew. They

have 5 children but never married.

A story my cousin told me of my grandmother taking him to

meet my grandfather, and coming home gave him a tot of something before putting

him to bed. My grandma was a force to be reckoned with. She was strong. A

district midwife. Someone described her as only looking after poor people. I

admire her because from her there is a list of midwives starting with my

mother, my niece and several others in the caring profession.

In 1956 I met my grandfather for the first time. It was a GCE

year, I was reading the book The 39 Steps. My favourite uncle took me to

see and meet my grandfather. He took me but not my sister, who looked like my

dad (my mum had married a black man). My grandfather said ‘you look like your

mother, come closer and sit by me’. Then he said a strange thing. ‘Your mother

was my favourite daughter, but I disowned her because she married a black man.’

I was so shocked I wanted to leave but my uncle said we could not leave, so we

spent another few days there. My uncle saw how upset I was, so he took us to

Downs River Fall to cheer us up. I never saw my grandfather again, although he

left me something in his will. My father was just as racist as my grandfather.

He had his own dry-cleaning business when he worked for the hotel, and the

white people, they paid; his friends did not pay, they were always paying

tomorrow.

The school I attended was a girls school with children from

America and Jamaica. We mixed very well. Yet when children became grown ups

life changed. Children mix together, they play together, then something

changes. We start to notice the colour of skin, who is rich or poor. God asked

us to share the wealth and bounty he gave us. Yet we don’t. So many refugees

have died trying to seek a better life. Do we see them as God’s people, or just

spongers? Why should we have to share with them? The world has become very

selfish. Coronavirus this year 2020, so many people were put in isolation. The

whole of God’s world was affected. For the first time churches, schools,

offices, etc were closed. We became afraid. Wondering if there was a cure or a

vaccine that could save lives. So far this has not happened. For a short time

we called it a world epidemic.

Lord, you

care for us, you gave us all we need. You ask us to look after the sick, feed

the hungry and homeless. Grant us Lord the wisdom to share all your bountiful

gifts, in Jesus’ name. Amen.

Reflection (Gloria Smith)

On reading the two bible

passages and Carlton’s reflection I am struck by the hope that is expressed in

all three. Not the kind of hope that the secular world believes in but

Christian hope that trusts that God is faithful, will never abandon us, and in

the end brings healing. I am always in awe of hope in the midst of destruction,

oppression and desolation – and this hope has been a recurring theme over the

last few weeks, even in the midst of some truly awful personal experiences.

I grew up in inner city

Winson Green in the ‘60s and I’m ashamed to say I lived in a home where racism

was commonplace. It was a strange world, because at school there were people

from many different cultures and from what I am able to remember it felt like

at school everyone was treated equally. That was my perception and maybe my

best friend Gloria Peters, an adopted black Caribbean girl, or Ranjit, a young

Sikh boy may have felt differently. But to me it felt different, more inclusive

than home.

Throughout my teaching

career, I have worked in inner city schools where the children were

predominantly from Pakistani/Muslims families. It took me a while to begin to

understand the issues they encountered, but it was made really clear when

taking the children out on trips. There would be strange looks and whispers

from schools with predominantly white children, and on more than one occasion I

felt it important to speak to other teachers about the way both children and

staff were responding.

For the most part, our

children really wanted to learn and we as teachers were given much respect by

parents simply for teaching their children. The gratitude was at times

overwhelming and it made me realise how important education can be. However on

reflecting now, it has also made me realise that although I was in the minority

because of my skin colour I was never ignored or treated negatively, which I

now understand is how my friends of colour often feel treated. I realise now how much was down to my

whiteness because Muslim teachers had far more difficult experiences when they

were perceived as not being as capable, than their white colleagues, even

within their own culture. They had to be outstanding to be acknowledged as half

decent. ‘White privilege’ is so damaging to people of colour.

In the final term of Year

1 at Queens theological college I learnt we would be doing a Black Theology module. I felt excited

because I felt I wasn’t racist and would enjoy the lectures. However, the

lectures and lecturers challenged that perception. At first I struggled with a

black lecturer who on occasions I felt at the time was oversensitive. She began

by telling us we would feel uncomfortable and would be challenged and that made

me feel defensive straightaway. I’m not keen on being told how I will feel! At

the time some other white students felt the same and it seemed to legitimise

our feelings – which can be quite dangerous – but looking back I think she was

simply preparing us for difficult topics that were to come. So now I ask myself

– So who really was feeling

oversensitive? The lecturers were really generous in sharing their own

stories, and as I read more and was prepared to really listen I got to

understand where they were coming from and what invaluable lessons we were

learning.

This is why I

passionately believe education to be so important in the healing of the nations.

At its best it gives opportunities for understanding other points of

view in a safe environment. It allows people to really hear what is being said

about experiences. But it is also important and necessary for history to be

told from the perspectives of all involved. British history has for far too

long been told from the white person’s perspective, the victors, the powerful.

Now more than ever children and adults too need to hear it from the point of

view of the powerless, the marginalised, the oppressed, the downtrodden, the

slave.

My hope is for that time

when all white people can really see things from the perspective of people of

colour and are prepared to stand alongside, acknowledge and make amends for the

past and move forward together. Then that heavenly vision in Revelation has a

chance of being realised.

Questions for reflection / discussion

As I read / listened to the

readings and reflections for this week…

·

what

did I notice, or what particularly stood out for me?

·

what

did they make me wonder, or what questions am I pondering?

·

what

have they helped me realise?

·

is there anything I want to do or

change in the light of this week's topic?

An Act of Commitment to the Work of Racial Justice:

People of

God, we stand in the line

of Moses, the prophets and the Christ,

crying out for justice and peace.

God calls us to be a people of reconciliation,

loving a world that is hungry, hurting and divided.

Courageous people have taken the risk

of standing up and speaking out

with those who have been pushed to the edges.

This work involves risking ourselves

for the sake of God’s love,

moving beyond ourselves

in order to discover and embrace Christ in one another.

We are all called to the work and ministry

of justice and reconciliation.

Therefore

let us join together

with people of faith and no faith throughout the world,

in committing ourselves today to racial justice:

I do.

· Do you support justice, equity and compassion in human relations, and liberation and flourishing for every person?

I do.

· Do you affirm that white privilege is unfair and harmful to those who have it and to those who do not?

I do.

· Do you affirm that white privilege and the culture of white supremacy which infest our nation and church must be dismantled?

I do.

Therefore, from this day forward:

· Will you strive daily to understand white privilege and white supremacy and how their existence benefits those among us who are white?I will.

· Will you commit to help transform our church culture to one that is actively engaged in seeking racial justice and equity for everyone?

I will.

· Will you make a greater effort to treat all people with the same respect that you expect to receive?

I will.

· Will you commit to developing the courage to live your beliefs and values of racial justice and equity?

I will.

· Will you strive daily to eliminate racial prejudice from your thoughts and actions so that we can better promote the racial justice efforts of our church?

I will.

· Will you renew and honour this pledge daily, knowing that out church, our community, our nation and our world will be better places because of our efforts?

I will.

[‘Racial Equity Pledge’, by First Unitarian Church of

Dallas, Texas;

adapted by St Francis Xavier Church, New York & Fr Robert Thompson]

Activities

/ conversation-starters with young (and not-so-young!) people

- In

today’s reading, we read: “the leaves of the trees are for the healing of

the nations.” Gather some leaves. Try to find as many different sizes,

shapes and colours as you can. As you hold each leaf, think of a person,

place or situation which needs healing, and hold them before God in

prayer. Let go of your leaf as a sign of handing over that situation to

God for healing.

- In

both our readings today, we read about the “river of life”. Find somewhere

you can put your hand into flowing water. If you can, use a river or

stream, but if you can’t get to one then putting your hand under a tap, or

asking someone to pour water over your hand would also work. What do you

notice about the feeling of water flowing over you? How does it make you

feel? I wonder what it life-giving about flowing water? I wonder what

situations you know of that need new life – in your own life, your

community, the church?

- Our

reading from Revelation includes a vision of the heavenly city as

somewhere where “death will be

no more; mourning and

crying and pain will be no more”. What other things do you think will be

‘no more’ in heavenly city? What would the perfect city be like? Write a

description and/or draw a picture.

[1] West

African proverb

[2] Tierno

Bokar, a Sufi Muslim who lived in Mali and was known as the Sage of

Bandiagara in the first half of the 20th century.

[3] Look up https://www.samanthalindo.com/blog-2/naming-the-water for a YouTube video of Samantha Lindo performing this song.

No comments:

Post a Comment